When Thomas Dadswell and his wife Helena Aurora Dadswell (nee Scheer) booked a boat passage to Australia in 1857, they chose to sail on the John Linn, one of the many sailing ships plying the England-Australia run to cater for the demand from people wanting to leave bleak conditions in Britain for what must have seemed very attractive opportunities in the gold-producing colony.

Tom and Helena were Dadswell ancestors who chose to try for a different, and hopefully better, life in Australia. Their migration resulted in the establishment of a branch of the Dadswell family which continues to this day.

They were part of a large movement of people from Britain to Australia, Canada and America. In the year prior to their travel, more than 16,000 people had migrated from Britain to the Colony of Victoria according to a report in The Times newspaper of London of 5 January 1857 - an average of 224 passengers per ship.

The voyage was often perilous; the recently-married Dadswells, both in their late 20s, did not know their ship would go dangerously close to disaster and that life on board would be made very unpleasant by overcrowding - one report had eight people allocated to one bunk for the duration of the three month-long voyage.

They travelled at a time when migration agents were advertising sailing passages to Australia at between 15 and 39 guineas (approximately $31.50 - $82) per adult, depending on the standard of accommodation.

Steam had yet to make an impact on the Australia run and the skippers of the sailing ships generally took the so-called Great Circle route, sailing south from Europe, rounding the Cape of Good Hope of southern Africa, and then seeking the 'Roaring Forties', the strong prevailing winds that blew from west to east between 40 and 50 degrees south.

But there were many hazards, including drifting icebergs and wild seas generated by storms. And even with skilled navigation getting ships successfully to Australian waters, many ships were still lost as they traversed the western coast of Victoria, a stretch of coastline now known as the shipwreck coast.

The ship chosen by the Dadswells, the John Linn, was only three years old, having been built in 1854 at Saint John, a Canadian centre in the north-east province of New Brunswick and which at that time had a significant ship-building industry.

Her hull was made from Tamarack pine and this had been sheathed in metal for added strength and robustness. She displaced 1,596 tons (1,470 tons according to some reports) and was described as a fully-rigged ship, meaning she most likely had three masts (but possibly more), with each mast carrying a set of square sails.

Initially she was owned by George King and John Storm, both shipbuilders in Saint John, but shortly before her 1857 voyage she was sold to Liverpool interests and this west-coast English city became her home port.

While the passenger manifest declared the John Linn was capable of carrying up to 365 adult passengers, her passenger list for the 1857 voyage declared she was capable (presumably provisioned) to carry 330 adults for 140 days. In reality, there were 347 passengers on board including 23 children aged 1 to 12, and 8 infants. She had a crew of 48, all British.

According to Melbourne birth records, two of the four infants born during the voyage survived the trip - Michael James Keogh, son of Thomas and Catherine (McIlroy) Keogh, and Kate Kennedy, daughter of Tim and Mary (Delaney) Kennedy, were on board when the ship arrived in Melbourne. Two unnamed infants, the sons of James and Margaret (Kennedy) Maher (Meagher), and of Mathias and Mary (Dollart) Owley (not mentioned on the passenger list), apparently did not survive their ship-board birth. One other infant, Mary Pfan, daughter of Feanz and Chris Pfan, died and was buried at sea.

[Above, a section from the John Linn passenger list. The last names on this page are "Thos Dadswell and Ellen Dadswell - why was Tom Dadswell's age recorded as 32 when he was only 28? Why was Helena called Ellen? Why were their nationalities (he was English, she was German) initially described as English, crossed out, and then recorded as Irish? Why was he recorded as a labourer when he would later claim to be an engineer? There are no obvious answers to any of these questions.]

Most of the male passengers were described on the passenger list as labourers or tradesmen, and they and their families were housed in steerage accommodation rather than in cabins. (Steerage accommodation was open space areas on the lowest decks. This area accommodated passengers travelling on the cheapest class of ticket and offered only the most basic amenities, typically multi-tiered bunks with limited toilet use, no privacy and mass-produced food).

For those on the John Linn, the demand for cargo space may well have also affected their living conditions - the ship carried a reported £23,000 ($46,000) worth of goods for those already living in the Colony of Victoria, cargo which may well have taken space which could otherwise have been made available to passengers.

It was a clash of competing needs that would result in passenger anger and, later in Melbourne, in court proceedings for the captain.

The John Linn left Liverpool on 26 June 1857. Her master for the 25,000 kilometre trip was William Henry Ray who had already made at least one trip to Melbourne, as master of the sailing ship Bellcarrigg in 1856.

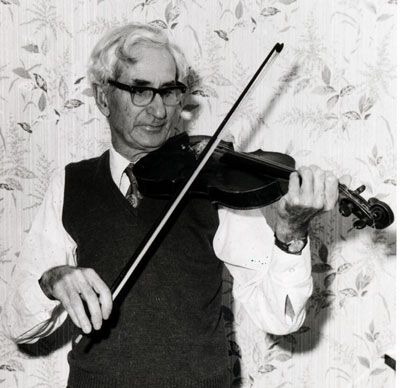

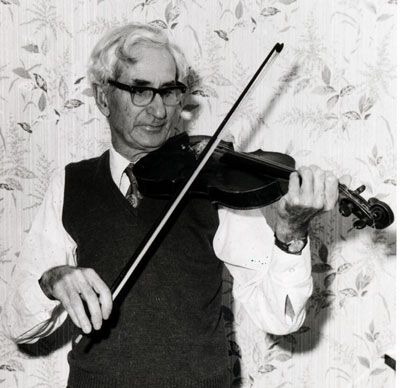

Family folklore has it that Tom Dadswell took aboard a violin which he bought at an insolvent's auction sale in London. Inside the violin was a label:

Made by James Perry

Back Lane

Kilkenny 1783 No 129.

During the voyage, Tom is said to have spent much of his time hand-making two replicas of this violin - the original violin and one of the replicas remains in the family today, more than 150 years after the voyage, while the second copy is no longer in the family.

[At right: The picture shows Tom Dadswell (1900-1985), a grandson of the emigrants Tom and Helena Dadswell, playing the original violin. The younger Tom played at concerts and in orchestras in Horsham, Stawell and Hamilton.]

While the Immigration Agent for the Colony of Victoria reported to Parliament in 1857 that the average length of an England-Melbourne voyage was 90 days, it became longer for those on the John Linn because of damage resulting from fierce storms.

On August 31, the ship ran into storms which tore away the fore and main topsail yards (the timbers which support the square sails) along with the main topmast tressel-trees (cross timbers supporting the mast structure). No loss of life as a result of the storm was reported and the damaged ship continued with limited sails.

In a later (2 October 1857) report in The Argus, published in Melbourne:

The John Linn left Liverpool on 26th June; experienced very light winds to the Equator which was crossed on the 36th day out in longitude 21W August 21st and then encountered a terrific gale from south west which carried away jib stay, sprung the main yard, fore and main topsail yards and broke the main topmast tressel trees. She passed Cape Otway at 3pm on the 29th and entered the Heads at ten am 30th ult.

When the John Linn docked in Hobsons Bay (Melbourne), she had completed a voyage of 101 days, or 3 months 4 days. While this was a longer than average time for ships of the day, Henry Dadswell (1894-1978, a grandson of Tom and Helena Dadswell) could remember a letter at his family's Warrak home, written by family back in England. It commented on the "exceptionally good" sailing time of three months.

It took some time for the ship to make its way down Port Phillip Bay and for port formalities to be concluded. But a short time later Tom and Helena were living in Vere Street, Collingwood, where their first child was born, in July 1858. While they no doubt had contact with fellow passengers during the trip, they probably had little or no further contact once they reached Victoria as after a short time in Melbourne the family moved to Geelong, and then to Western Victoria.

But the woes of the ship were not over. Two of the crew deserted the ship in Melbourne - Patrick Orkney (also known as Patrick Aughney), a 38-year-old steward, and David Donaldson, a 32-year-old carpenter, left the ship on October 4 and did not return. Both were from Ireland.

As well, many passengers complained about the living conditions on the voyage and William Ray, as Master, was required to appear in Williamstown Police Court to answer "berthing charges".

The Argus of 8 October 1857 reported:

W. H. Ray, master of the ship John Linn, from Liverpool, appeared to answer the complaint of Charles Broad, Esq., Immigration officer, for the improper berthing of the passengers. Mr. Read appeared for the defence. A large number of passengers were in attendance. From the evidence it appeared that the ship was chartered by Mr. Edward Thompson, of Liverpool, the same person who chartered the Dragoon, and that the same disregard to the requirements of the act as to berthing the passengers (two men being in the same berth) had been evinced in the case as in the former. Four cases were only got through when the Court adjourned until Monday, inflicting a penalty of 5 pounds and costs in each case.

On Monday, the 6th, the Bench again resumed the hearing of tho case, when Mr. Broad called Thomas Moscoff, who proved that the berth he occupied was shared by another man, and that underneath them a married couple were placed. The Bench inflicted a penalty of 40 pounds and costs, one moiety [compensation] to the witnesses in attendance, Mr. Broad withdrawing the other cases. He, however, stated that a girl who had been berthed with seven men during the voyage had been obliged to leave Melbourne or he would have gone into her case.

It would be early November before the John Linn could sail again - she departed for Sydney and Callao, Peru, with no cargo, and made a return to Melbourne in 1859 with another cargo and about 124 passengers. This time her voyage took 120 days and again she left for Callao with no cargo.

Before her 1857 trip, the John Linn had featured in a dramatic rescue of crew and cargo. According to the Moreton Bay Courier of 8 November 1856, a party from the John Linn put to sea in boats in the dark and in rainy weather when they came across an American clipper ship, the Golden Gate, ablaze. Their rescue efforts won praise.

Sadly, fire also would also be the fate of the John Linn. In September 1863, the ship left Bombay with a valuable cargo of cotton destined for English mills. She had been making her way up the western coast of Africa but encountered storms which damaged the ship. From a Board of Trade inquiry, as reported by The Times of 10 March 1864:

... the 7th of December ... they found she had sprung a leak, and that the water was fast rising in the hold. The men worked hard at the pumps. On the 27th December they signalled a vessel called the Clyde, bound for London, and the men wished to leave the ship and go on board the Clyde. The captain [of the John Linn] refused to do so, and the Clyde sailed away. The men at first refused to work but when the Clyde disappeared they returned to their duty. They threw overboard part of the cargo, and worked incessantly at the pumps, but still the water gained on them, and when, on the 1st of January, the French bark Felix Bernardo, Captain Hector, hove in sight, they felt that their only hope was to abandon their ship.

The French ship landed the crew at Martinique in the West Indies, and from there they were repatriated back to England.

In the meantime, a non-British ship, the Deogaum (also reported as Deageum), Captain Beaglehole, travelling from Pernambuco (Brazil) to Hamburg, came across the abandoned John Linn. A crew boarded her and found about 3½ feet (about 1 metre) of water in the hold and the pumps choked. Part of the cargo was recovered to their own ship and the boarding party then sailed the John Linn for a short time but found they had insufficient crew. The decision was made to abandon her.

According to evidence given to the Board of Trade, the mate of the Deogaum, on his own authority, set fire to the vessel, giving as his reason that she might fall foul of some other ship. They saw her burning for some hours after they left her, and "there could be no doubt that she was consumed."

In a further report in The Times (15 March 1864), the Board of Trade attacked the actions of the master of the Deogaum and added:

... the Court is satisfied that Captain Browning and his crew used every exertion to get his ship home or into a port of safety, and only abandoned her in extremity, and when he considered it necessary to save life, and after 24 days of unremitting exertion....

The Court desires to express its opinion that the mate of the Deogaum had no business to set fire to the ship, as he did, on his own responsibility ....

The "death" of the John Linn was cause for comment, both at the time and a decade later in 1874, when Harper's New Monthly Magazine published a story critical of British ship owners sending to sea ships which were clearly unseaworthy. It read, in part:

Do men consciously send ships to sea knowing them to be unseaworthy? A Liverpool underwriter recently stated before an official committee that certain vessels were so bad that the companies there refused to insure them. "They are a sort of black sheep," he said; and in eleven years there was on the underwriters' list in Liverpool alone a considerable flock of these black sheep, no less than 225; of these thirteen were wrecked during that period, eleven were abandoned at sea, three foundered, and six were condemned, and mostly, we read, "sold to foreign owners," to begin a new career under some other flag, and drown other poor Toms [sailors]. There appears to be even a regularly organized business in sending to sea unseaworthy ships.

In the magazine's list of ships lost at sea:

1863 - John Linn, wooden sailing vessel, abandoned at sea, coming home from Bombay. No lives lost.

Further reading

Further information about Tom and Helena Dadswell is on this website.

There are a number of information sources which tell parts of the story of the John Linn - if you know of additional information, please share the knowledge by emailing or mailing Harley Dadswell at PO Box 519, Curtin ACT 2605, Australia.

For a list of sources used to prepare the above article, see Further reading, the John Linn.

- Information compiled October 2009, updated 4 Nov 2009 Return to Family Stories Index Page

|